Hope

A firm and well-founded belief that things will be better

Picture: Martina Stokow

Content

Some information is important, some interesting, and all has a degree of uncertainty. Some information we trust and make decisions upon. If we restrict ourselves to the important and the interesting, and we can reduce the uncertainty, then we will make better decisions. We may also enjoy the venture.

"Even a fool may be thought wise and intelligent if he keeps his mouth shut"

Prov. 17:28

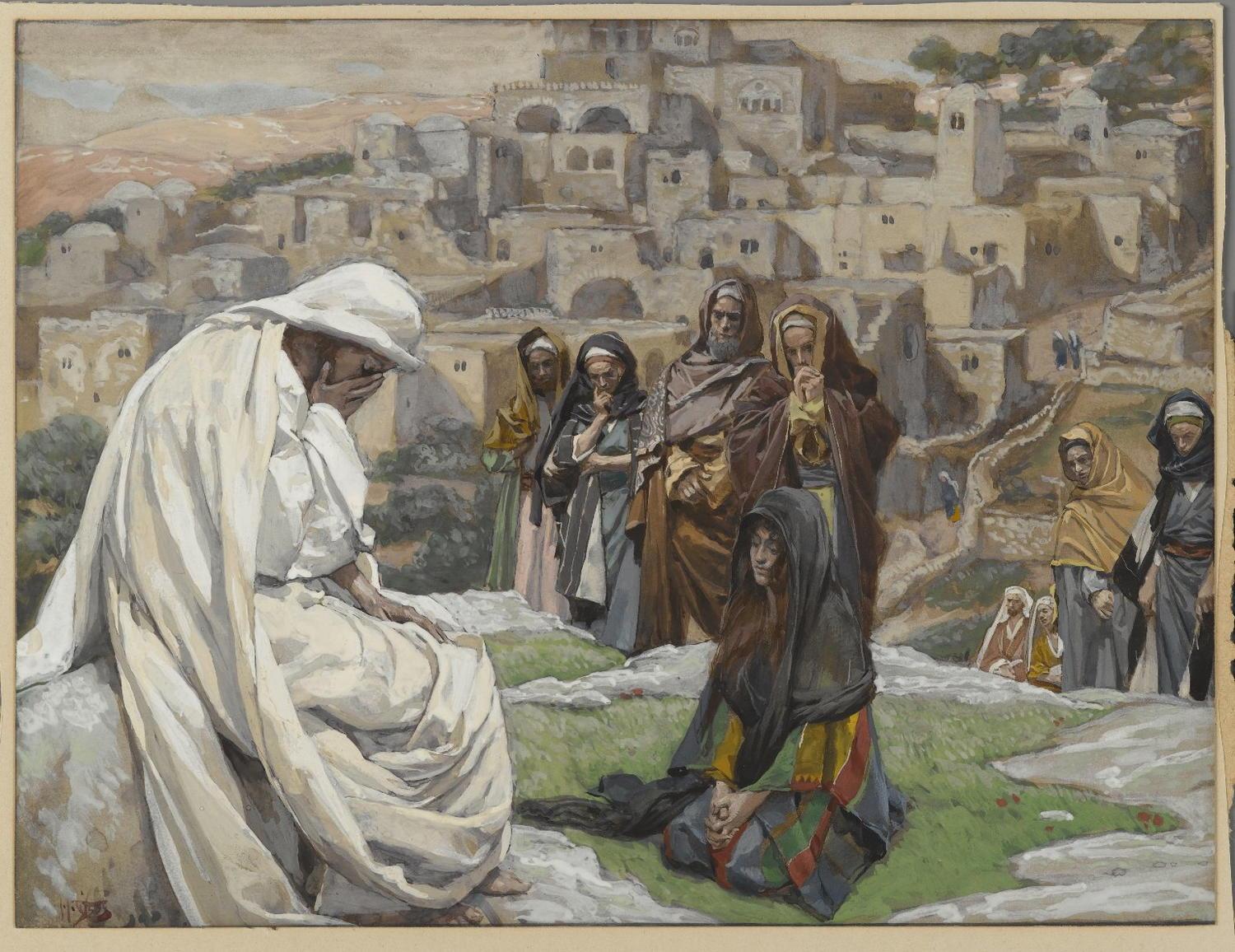

James Tissot - Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ

James (Jacques) Tissot lived in the 19th century and was a French painter of high society fashion and portraits. He had as contemporaries Monet, Degas and Van Gogh. Van Gogh said of him in 1880 "Some profound critic rightly said of James Tissot ‘He’s a soul in need’. But in any event, there’s something of the human soul there; it’s for that reason that that is great, immense, infinite" (ref). In 1885, however, Tissot experienced two visions; one of his late Irish mistress, the love of his life, and one, while painting socialites in the Cathedral of Saint Sulpice, of Our Lord Jesus Christ, telling Tissot that 'without Me, civilisation is a ruin' (ref). This changed his life completely and he spent the next ten years devoting himself to researching and documenting the truth about the life of Jesus, with a particular interest in accuracy. He was immediately astonished that almost all historical depictions of Golgotha, or Mount Calvary, the site of the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, were grossly inaccurate, along with most other renditions of the Holy Land. While the artists or historians had perhaps tried to convey a sense of piety and awe, Tissot felt that this hindered his appreciation of Our Lord; He needs no veneer. In the 1880s and 1890s Tissot produced a epic work of two volumes and 365 colour illustrations (plus many more minor illustrations) depicting, with the greatest accuracy possible to him, the scenes of the Gospels and of the people, buildings and environment of the Holy Land, before it had been spoiled by 'the invasion of the engineer and the railway' (Tissot, 1897). These met with extraordinary acclaim - along with some criticism, mainly that the style was too exact in its depiction - and the majority of the collected works were deposited in the Brooklyn Museum in New York, where they remain.

Jesus among the desolate poor

Jésus Pleura - Jesus Wept

My interest in Tissot began when I was searching for public domain religious images to use in internet content during COVID, when churches were closed. I came across his painting 'Jésus Pleura' and was immediately struck by it. The scene is Jesus' arrival at Bethany where Lazarus has died. A woman is knelt at his feet in great sorrow, along with others nearby, and the village pictured behind it. It is beautiful; it portrays a striking figure of Jesus Christ. But what is vital here, for me, is that Jesus is not crying for the dead Lazarus. Lazarus and his tomb are not in the picture. According to the Gospels, after hearing the news of Lazarus' death, Jesus has deliberately waited so that four days have passed before He arrives at the house of Lazarus 'whom He loved'. He does not cry until He reaches the mourners at the grave. I have heard several say that He is crying for the natural human pain of losing a loved one, and even the Brooklyn Museum subtitles this piece in this way (ref), but that cannot be so - He is about to bring Lazarus back from the dead to everyone's great joy and amazement. Indeed John precedes this with "When Jesus therefore saw her weeping, and the Jews also weeping which came with her, he groaned in the spirit, and was troubled", and this 'groaning' is the Greek 'embrimaomai' meaning strong indignation and rage (e.g. ref). Just before that, Jesus has asked Martha whether she believes Lazarus can be raised from the dead and tells her "Thy brother shall rise again" but she thinks Jesus means the resurrection at the last day; her hope is partial, yet Jesus is limitless. Martha has given up hope that Jesus will raise Lazarus now, after four days - after all, the body will be decomposed and everyone knew that the spirit did not stay with the body more than three days. Remember also that over and over again Jesus has been telling them that with belief in Him, anything is possible. So for me - and I emphasise this is my own view - His tears and frustration on seeing the weeping women are because, as their loving shepherd, it is unacceptable that His flock should be so oppressed by death or subject to such fear and despair as the world presents; there should be no death, and no weeping. They don't fully understand (or believe, or trust) yet the depth of his power. For me, it is indeed the power of God that is palpable here, and He feels all of our injuries and wishes them to be gone.

"Jesus said unto her, I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. Believest thou this?" *

Continue reading about James Tissot's work and insights...

* Why quote from the King James Version of the Bible?

I don't have any particularly strong feelings about any English version of the Bible. For now, I am using the (old) King James Version for two main reasons. One is because, along with the (old) English Book of Common Prayer, it contains many phrases that have entered the common language and are very memorable. The other is because its old form of English has become 'elevated' over time; that is to say the reader immediately knows they are hearing some important words most likely from the Bible, and it reminds them of the elevated nature of God. Isaac Asimov, in his book "In the Beginning: Science faces God in the Book of Genesis" also quotes only from the King James Version. As he puts it, for translations, "none can match the King James Version for sheer poetry". Please do not get caught up on this; read any Bible you like, and remember that every one is a translation by a committee with one outlook or another, and if you get stuck, it is likely that you will learn a good deal more by finding out what original Greek, Hebrew or Aramaic word or phrase was actually used. By the way, we almost all still use an Aramaic word now - Amen. If you want to dive into the deep end, search 'Strong's interlinear', or find out what 'epiousios' or 'adelphos' means.